WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO THE FOOD PYRAMID?

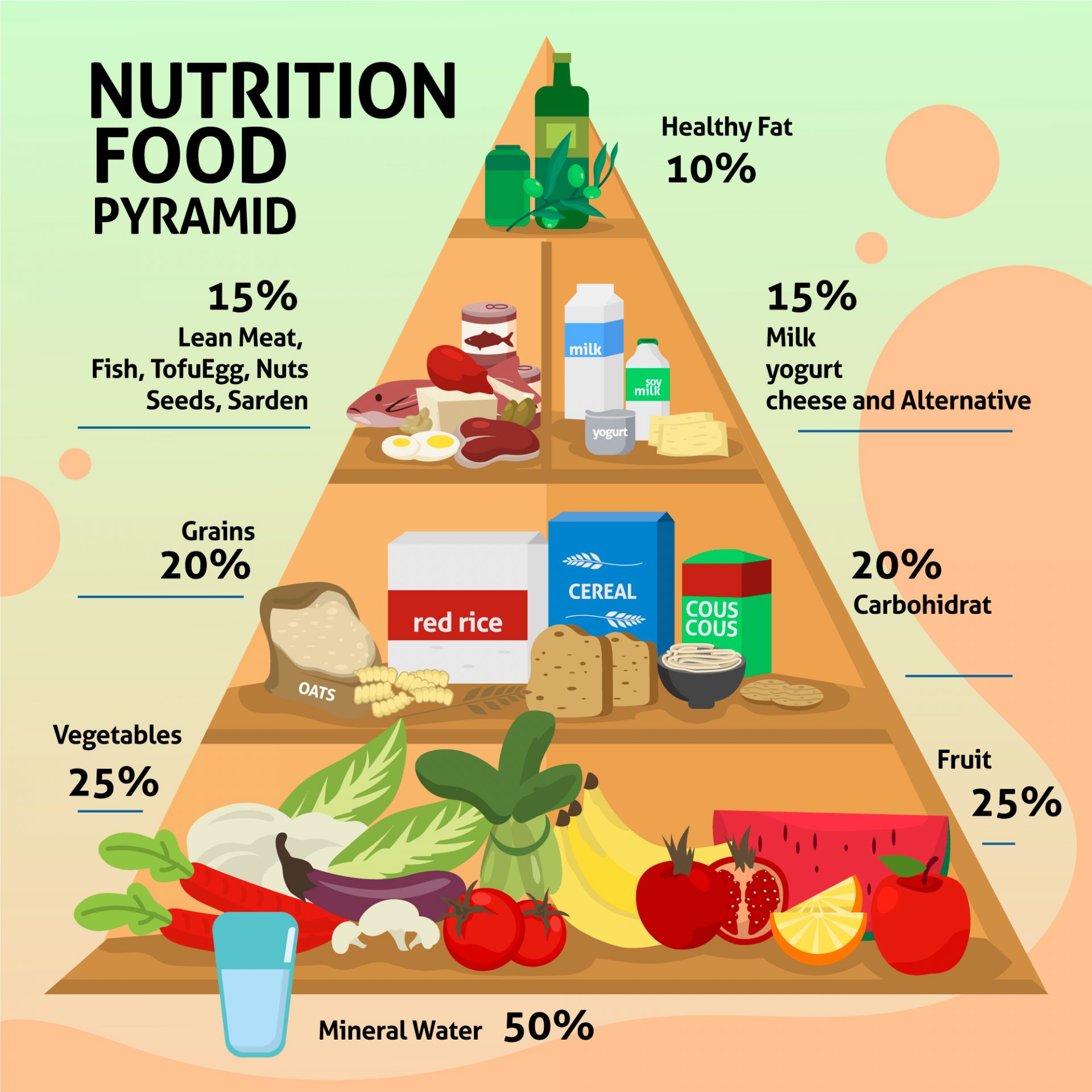

The Food Guide Pyramid was introduced by the USDA in 1992 and gave millions of Americans a visual picture of what to eat. The pyramid’s base, which included grains, recommended 6–11 servings of grains daily. It showed fruits and vegetables at the bottom of the pyramid, followed by protein and dairy, fats, oils, and sweets at the top, with the advice to “consume sparingly.”

In place of stacked categories, the food pyramid was revised in 2005 to show vertical slices. And in 2011, MyPlate, a new recommendation symbolized by a plate divided into vegetables, proteins, fruits, grains, and dairy, officially took its place. This updated guide was created with the consumer in mind: You may easily prepare a nutritious dinner by just filling your plate, as the illustration depicts.

Five experts discuss the Food Pyramid, MyPlate, and how we should eat today in the sections below.

WHAT THE PYRAMID GOT RIGHT

The pyramid had a purpose, even if it was no longer the favoured option. According to Amy Goodson, RD, MS, “The Food Guide Pyramid did instruct as to what should be the core components to the diet, such as whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.” It also instructed us to eat a variety of food groupings.

According to Liz Wyosnick, MS, RD, proprietor of Equilibriyum, a private nutrition clinic in Seattle, all foods may be included in a balanced eating pattern. “All you have to do is eat the right meals in the right amounts,” For instance, the pyramid positioned high-sugar foods at the very top to signify that they should make up a minor proportion of your diet overall. However, most servings were made up of fresh vegetables and healthy grains, highlighting how important these foods are to your diet. “If you give the food pyramid any thought, there is a beautiful metaphor. As a pyramid’s strength and integrity derive from its solid base, so too does our health’s strength come from a foundation of nutrition based on fresh, complete veggies, says Wyosnick. She points out that although the pyramid metaphor may have failed, it had good intentions.

WHERE THE FOOD PYRAMID FAILED

The proprietor of Active Eating Advice, Leslie Bonci, RD, MPH, asserts, “No one eats a meal in the shape of the pyramid.” Some others read it top down rather than bottom up because the topics were difficult to understand and envision. She also points out that the pyramid’s food advice was universal, even though everyone had different dietary requirements. “Six to 11 servings of grains daily does not always mean 11 for everyone.”

When the Food Guide Pyramid was published in 1992, the nation was engrossed in a no-fat/low-fat obsession. According to Melissa Macher, RD, LD, proprietor of A Grateful Meal, the ambiguous advice to utilize all fats “sparingly” was a crucial weakness in the pyramid. Nuts, avocados, or fish high in omega-3 fatty acids—foods we know to have healthful fats—were not exempted from the rule. Macher continues, “There was also no clear differentiation between fibre-rich, complex carbs and simple carbohydrates.” The public message and overall efficacy were weakened since the reduced pyramid did not allow for crucial differences.

According to Samantha Cassetty, MS, RD, a nutrition and wellness specialist and co-author of Sugar Shock, “science has shown that people who limit their fat intake, including their intake of healthy fat, and eat a heavy carbohydrate diet, which is the pattern promoted by the Food Pyramid, tend to have unhealthy cholesterol and triglyceride levels.” This diet can worsen heart disease and hurt your good and harmful cholesterol levels. “We have clarified much of the information provided in the Food Pyramid, and we know a lot more about foods and eating behaviours connected with improved health outcomes.”

The Food Pyramid was also unclear.

For instance, Cassetty points out that the vegetable objectives were minimums while the protein requirements were maximums. Consumers were likely to overlook this disparity unless they carefully studied the facts. While the recommendations were not inherently harmful, Wyosnick argues that they were challenging to understand and apply to inform consumer food choices effectively.

The pyramid sparked the food-related conversation, which may have overall positive effects. But the pyramid’s fundamental principles inevitably pitted one category against another.

According to Macher, the stacking of the food groups, especially in the 1992 iteration, reinforced a dichotomy of “good” and “bad” food, which undoubtedly didn’t assist Americans’ connection with food. Instead, it solidified a moral aversion to some meals.

MOVING TO MYPLATE

It’s normal for nutritional advice to change with time, just like medical advice does. According to Cassetty, the USDA’s dietary recommendations have changed over time, and the images on MyPlate now reflect our most current knowledge of nutrition and health.

Several of the problems from the Food Guide Pyramid are addressed with MyPlate. For instance, lipids are not limited to a tiny sliver at the top of the plate and vegetables are given a more significant portion of the meal than grains. Instead, dairy is placed adjacent to the dish to complement meals. “A more consumer-friendly representation for teaching and implementation,” claims Bonci. As a result, everyone can comprehend the plate image, even though it is still too simplistic.

According to Wyosnick, who builds the bulk of her meals using the balanced plate model: half vegetables, quarter complex carbs, and quarter protein, “I enjoy this picture because it is much more realistic and simpler to implement on a meal-by-meal basis.” In addition, “I know it is beneficial in terms of macro- and micronutrients.”

MyPlate is imperfect, though. MyPlate has come under fire for having too much involvement in the food industry, and Macher notes that its guidelines still don’t completely take into account the intricacies of dietary fat. She suggests Harvard’s Healthy Eating Plate as an option since it provides more context than MyPlate and has images of water consumption and physical activity.

Despite preferring to provide far more customized suggestions to her customers based on their interests and background, she admits that she enjoys utilizing a plate image as a teaching tool. “It is challenging to condense the complexities of food and nutrition from a scientific and cultural perspective into a generalized strategy. The plate approach is an excellent place to start. Still, the most extraordinary long-lasting answers will likely come from consulting experts who can consider your physical health and your mental and emotional health, preferences, and cultural norms.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Though well-intended, the Food Guide Pyramid is no longer the recommended eating strategy. MyPlate helps you get closer to a balanced diet, but there are a few accepted methods for eating well, regardless of whether you believe in pyramids, plates, or something else. Generally speaking, it is recommended to concentrate on eating fresh vegetables, lean meats, whole grains, dairy products, and healthy fats. To guarantee a nutritious diet, consume foods from all dietary categories.

Remember that these are objectives, but don’t let them demoralize you if your eating patterns fall short of them, advises Cassetty. “You may change your diet in simple ways. Set a goal, for instance, to drink water instead of a sugary beverage or munch on fruit and nuts rather than a boxed snack. You don’t have to eat well all the time, and everyone has a right to indulge in things they like occasionally. However, even modest moves toward developing healthy eating practices indicate that you are moving in the right direction.